by Peter Tracy

Whether it be pop, rock, punk, or bossa nova, the guitar is a staple of many of the musical styles we know and love—and it has even carved out a unique niche in contemporary classical music as well. For guitarists, bridging and fitting into the many genres and styles of guitar-playing can be a daunting task, but Mary Halvorson and John Dieterich are well-equipped for the challenge.

On their new collaborative album a tangle of stars, the guitarists draw on the genre-crossing versatility of their instrument, coming forward with a wide-ranging album that is somehow grooving, mellow, sharp, and aggressive all at the same time.

That Dieterich and Halvorson are collaborating at all can seem like something of a miracle. As a member of the popular noise-rock band Deerhoof, Dieterich has become a renowned and influential guitarist, but it wasn’t until 2017 that he met Halvorson, whose work as a composer and bandleader in avant-garde jazz has earned her widespread praise. A completely improvised live set on acoustic guitars led to further collaboration in Dieterich’s home studio, where they co-composed, arranged, and recorded a tangle of stars over the course of three days, resulting in a collaborative album that mines their mutual interest in experimental jazz, pop, rock, noise, and improvisation.

With various types of guitars including acoustic, electric, 12-string, and baritone, as well as countless effects and occasional drumming by Dieterich, the album provides a wide range of emotions and styles. “Drum the Rubber Hate,” for instance, kicks off with a spinning, plucky, and bright theme supported by a grooving baseline. Quickly, though, a steadily ascending, almost classically minimalist baseline is introduced, making room for virtuosic solos that strike a balance between the rhythmic complexity of jazz and the distorted, edgy sounds of rock music. “Balloon Chord” provides a totally different mood: warm acoustic arpeggios support a flinty, picked melody that seems to wash into the droning background of reverb and watery effects. The wall of reverb sometimes takes on an uneasy edge, making for a song that is somewhere between atmospheric and unsettling.

The duo take a totally different approach on “Short Knives,” a tense song featuring sharp, stabbing strums that bend in pitch and explode into winding, dissonant passages of warped electric guitar. Despite the occasional rough edges, though, the album also provides plenty of warmth: “Lace Cap,” for instance, is a reassuringly melodic and lilting track with relaxed arpeggios and bended notes, making for a watery, off-kilter sense of calm. “Vega’s Array” is another moment that feels more relaxed and playful: here, an intricate background of contrasting guitar timbres swings underneath wandering melodic lines and plenty of odd little slides reminiscent of shooting stars.

On the noisier, more experimental side of things, “The Handsome” is full of wailing, distorted electric guitars that imitate each other almost like a canon, phasing in and out of sync before being swallowed up by distortion. The last third of the track becomes increasingly frantic, as the guitars get more rapid and static-filled before giving way to stuttering electronic effects that sound like a record scratching and skipping.

“Better Than the Most Amazing Game” is the album’s longest track by far, and is another moment on the album that feels close to the worlds of avant-garde and free jazz. Here, mechanical, almost industrial effects and drums collide to form an off-kilter and unsettling beat ridden by freely wandering guitar chords and melodies. These elements never quite seem to settle into a stable groove, and the whole track stops and starts jerkily, making for what sounds like an amazingly unhinged piece of music created by a computer program. “Continuous Whatever” brings us into another world yet again, ending the album with a short and sweet bit of relaxed guitar counterpoint.

Despite these rapid-fire stylistic shifts, though, Halvorson and Dieterich manage to craft a cohesive album out of their many musical influences. With its thrilling sonic detours and stylistic excursions, a tangle of stars reflects the huge and tangled variety of music being made for guitar, and speaks to the versatility of not only the instrument, but the composers and performers themselves.

Clarinetist, saxophonist, and composer Ken Thomson is known primarily for his work with the Bang on a Can All-Stars. But as it turns out, he’s been living a sort of musical double life as a jazz musician for, basically, ever, much like Ron Swanson as

Clarinetist, saxophonist, and composer Ken Thomson is known primarily for his work with the Bang on a Can All-Stars. But as it turns out, he’s been living a sort of musical double life as a jazz musician for, basically, ever, much like Ron Swanson as

Over the course of the past decade, the four composer-performers who make up the Hands Free have performed together in a variety of contexts. They found that what they loved doing the most was holding informal late-night jam sessions—which is what led to the quartet’s inception. Comprised of violin, accordion, bass, and guitar (plus the occasional banjo), the ensemble likes to perform unamplified, sit in a circle, and integrate a mix of genres ranging from folk music to jazz and improvisation. Their resulting debut album features a beautifully eclectic mix of sounds that depict an immense variety of places and emotions—all while maintaining the warmth and spontaneity of an impromptu jam session.

Over the course of the past decade, the four composer-performers who make up the Hands Free have performed together in a variety of contexts. They found that what they loved doing the most was holding informal late-night jam sessions—which is what led to the quartet’s inception. Comprised of violin, accordion, bass, and guitar (plus the occasional banjo), the ensemble likes to perform unamplified, sit in a circle, and integrate a mix of genres ranging from folk music to jazz and improvisation. Their resulting debut album features a beautifully eclectic mix of sounds that depict an immense variety of places and emotions—all while maintaining the warmth and spontaneity of an impromptu jam session.  Anna Thorvaldsdottir finds inspiration in nature—her music is its own ecosystem, the nuanced textures shared, traded, and transformed among individual instruments over the course of her works.

Anna Thorvaldsdottir finds inspiration in nature—her music is its own ecosystem, the nuanced textures shared, traded, and transformed among individual instruments over the course of her works.  This beautifully-produced

This beautifully-produced  Paddle to the Sea was a book that was made into a movie that was made into a live show and album by Third Coast Percussion. In Holling C. Holling’s original 1941 children’s book, a First Nation boy in Ontario carves a wooden canoe and on its side, he writes “Please put me back in the water. I am Paddle-to-the-Sea.” He puts the boat into the Great Lakes where it begins its adventure, and the book follows it on its journey. (Spoiler alert: years later, the boat winds up in a newspaper story that ends up in the hands of the boat’s original creator, who is by then a grown man.) The film, which was released in 1969, added a focus on water pollution to the original story.

Paddle to the Sea was a book that was made into a movie that was made into a live show and album by Third Coast Percussion. In Holling C. Holling’s original 1941 children’s book, a First Nation boy in Ontario carves a wooden canoe and on its side, he writes “Please put me back in the water. I am Paddle-to-the-Sea.” He puts the boat into the Great Lakes where it begins its adventure, and the book follows it on its journey. (Spoiler alert: years later, the boat winds up in a newspaper story that ends up in the hands of the boat’s original creator, who is by then a grown man.) The film, which was released in 1969, added a focus on water pollution to the original story.

Drawing inspiration from the experiments of Leonardo da Vinci, facial polygraphs, and more, Invisible Anatomy’s

Drawing inspiration from the experiments of Leonardo da Vinci, facial polygraphs, and more, Invisible Anatomy’s

As an avid hiker, I couldn’t resist Vincent Raikhel’s Cirques. A reflection of the glacial geological formations so often encountered in the Cascade Mountains, this piece immediately transported me to a faraway corner of the imposing mountain range in Seattle’s backyard. In the context of the Spooky Music Marathon, this piece made me think of the creeping claustrophobia that one might feel in a cirque, especially as the sun sets, as it does so quickly in the mountains. It’s curious, how something so open to the sky, so large and static, can suddenly feel as if it is closing in on you in the waning light… –

As an avid hiker, I couldn’t resist Vincent Raikhel’s Cirques. A reflection of the glacial geological formations so often encountered in the Cascade Mountains, this piece immediately transported me to a faraway corner of the imposing mountain range in Seattle’s backyard. In the context of the Spooky Music Marathon, this piece made me think of the creeping claustrophobia that one might feel in a cirque, especially as the sun sets, as it does so quickly in the mountains. It’s curious, how something so open to the sky, so large and static, can suddenly feel as if it is closing in on you in the waning light… –  It just wouldn’t be a Halloween marathon without a spooky clown—and Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire is nothing if not haunting. A masterpiece of melodrama, the 35-minute work tells the chilling tale of a moonstruck clown and his descent into madness (a powerful metaphor for the modern alienated artist). The spooky story comes alive through three groups of seven poems (a result of Schoenberg’s peculiar obsession with numerology), each one recited using Sprechstimme: an expressionist vocal technique that hovers eerily between song and speech. Combine this with Schoenberg’s free atonality and macabre storytelling, and it’s enough to transport you to into an intoxicating moonlight. –

It just wouldn’t be a Halloween marathon without a spooky clown—and Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire is nothing if not haunting. A masterpiece of melodrama, the 35-minute work tells the chilling tale of a moonstruck clown and his descent into madness (a powerful metaphor for the modern alienated artist). The spooky story comes alive through three groups of seven poems (a result of Schoenberg’s peculiar obsession with numerology), each one recited using Sprechstimme: an expressionist vocal technique that hovers eerily between song and speech. Combine this with Schoenberg’s free atonality and macabre storytelling, and it’s enough to transport you to into an intoxicating moonlight. –

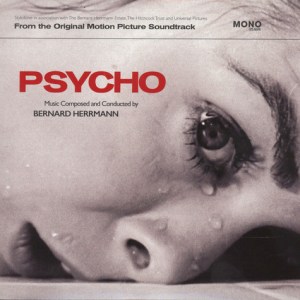

This piece is so timelessly cool and undeniably scary. Like John Williams’ Star Wars score borrowed the dark side of the Force from the dojo-dominating “Mars, the Bringer of War” in Holst’s The Planets, Herrmann borrows the creepy suspenseful stringiness of Norman Bates from the dancing skeletons in Camille Saint-Saens’ Danse Macabre (and maybe from Mussorgsky’s Bald Mountain witches).

This piece is so timelessly cool and undeniably scary. Like John Williams’ Star Wars score borrowed the dark side of the Force from the dojo-dominating “Mars, the Bringer of War” in Holst’s The Planets, Herrmann borrows the creepy suspenseful stringiness of Norman Bates from the dancing skeletons in Camille Saint-Saens’ Danse Macabre (and maybe from Mussorgsky’s Bald Mountain witches).

I have to admit: this Staff Pick was a tough choice for me. It was a toss-up between Richard Reed Parry’s For Heart, Breath and Orchestra, and Christopher Cerrone’s How to Breathe Underwater. In one corner, a piece by a guy from one of my favorite bands, wherein he had musicians and the conductor listen to their own heartbeats through stethoscopes and asked them to play along as closely as possible to their own heartbeats—a beautiful existential notion and a beautiful thing to listen to.

I have to admit: this Staff Pick was a tough choice for me. It was a toss-up between Richard Reed Parry’s For Heart, Breath and Orchestra, and Christopher Cerrone’s How to Breathe Underwater. In one corner, a piece by a guy from one of my favorite bands, wherein he had musicians and the conductor listen to their own heartbeats through stethoscopes and asked them to play along as closely as possible to their own heartbeats—a beautiful existential notion and a beautiful thing to listen to. In the other corner, a piece that’s kind of about depression, which is based on a Jonathan Franzen character from the book Freedom, of whom Franzen said, “[she] was all depth and no breadth. When she was coloring, she got lost in saturating one or two areas with a felt-tip pen.” If you are not weeping by the end of that sentence and by the end of this heartbreakingly hopeful piece, check your pulse, man. Ultimately, I loved them both so much that I had to just close my eyes and pick one. But…oops! I wrote about both of them. Now you’ll never know which one I picked! –

In the other corner, a piece that’s kind of about depression, which is based on a Jonathan Franzen character from the book Freedom, of whom Franzen said, “[she] was all depth and no breadth. When she was coloring, she got lost in saturating one or two areas with a felt-tip pen.” If you are not weeping by the end of that sentence and by the end of this heartbreakingly hopeful piece, check your pulse, man. Ultimately, I loved them both so much that I had to just close my eyes and pick one. But…oops! I wrote about both of them. Now you’ll never know which one I picked! – “Every city produces its own set of harmonies,” Michael Gordon writes in his program note for this piece. In Beijing Harmony, those chords are dazzling and majestic, shimmering magnificently across the orchestra.

“Every city produces its own set of harmonies,” Michael Gordon writes in his program note for this piece. In Beijing Harmony, those chords are dazzling and majestic, shimmering magnificently across the orchestra.