Second Inversion hosts share a favorite selection from their weekly playlist. Tune in on Friday, September 15 to hear these pieces and plenty of other new and unusual music from all corners of the classical genre!

William Brittelle: Hieroglyphics Baby (New Amsterdam)

If you’re looking for some Friday night grooves, William Brittelle’s got the tune for you. “Hieroglyphics Baby” is a colorful art-pop-meets-classical mashup from his full-length, lip-synched (when live) concept album Mohair Time Warp. Tongue-in-cheek lyrics spiral through Technicolor melodies in this art music adventure that splashes through at least six musical genres in the span of three minutes. See if you can keep up. – Maggie Molloy

If you’re looking for some Friday night grooves, William Brittelle’s got the tune for you. “Hieroglyphics Baby” is a colorful art-pop-meets-classical mashup from his full-length, lip-synched (when live) concept album Mohair Time Warp. Tongue-in-cheek lyrics spiral through Technicolor melodies in this art music adventure that splashes through at least six musical genres in the span of three minutes. See if you can keep up. – Maggie Molloy

Tune in to Second Inversion in the 12pm hour today to hear this piece.

Harry Partch: “The Wind” (Second Inversion Live Recording)

Charles Corey, Harmonic Canon II and Melia Watras, bass marimba

Having the Harry Partch instrument collection in Seattle is a benefit that cannot be overstated. I’ve attended many of their concerts at this point, and after every single one, I walk away feeling that my ears have been stretched in a pleasant and healthful manner. I could call the experience “musical yoga” or “aural vegetables,” but no matter how I describe it, it seems clear to me that listening to Partch, in any form, is one of the best things one can do for their listening skills. – Seth Tompkins

Tune in to Second Inversion in the 4pm hour today to hear this piece, and watch our live video below!

Terry Riley: Fandango on the Heaven Ladder

Gloria Cheng, piano (Telarc Records)

Terry Riley says of his Fandango on the Heaven Ladder, “It is no secret that I am wild about the music of Spain and Latin America, and since I heard my first fandango I’ve been wanting to write one. In Fandango on the Heaven Ladder, I am attempting to alternate and somewhat fuse the controlled sensuality of the romantic fandango with a somewhat melancholic chorale.”

Terry Riley says of his Fandango on the Heaven Ladder, “It is no secret that I am wild about the music of Spain and Latin America, and since I heard my first fandango I’ve been wanting to write one. In Fandango on the Heaven Ladder, I am attempting to alternate and somewhat fuse the controlled sensuality of the romantic fandango with a somewhat melancholic chorale.”

The piece weaves in and out of fandango and melancholy, giving the impression of moving from solitude into a dreamlike soirée, only to slip back inward while stepping outside into a glassy night and hearing the sounds of the party flow out through the windows and doors. – Brendan Howe

Tune in to Second Inversion in the 7pm hour today to hear this piece.

Bruce Adolphe: Night Journey (Albany)

Musical Arts Woodwind Quintet

Any composer who sets out to write a really good wind quintet contends with inherent challenges of the instrumentation, chief among them the balance of sound between the high, light sound of the flute and the potentially low and overwhelming sound of the French horn. But they also have a beautiful, diverse palette of colors and textures open to them, and it seems to me that this 1986 work for winds makes use of these with aplomb. It’s a very enjoyable piece that moves in three main sections through bubbly counterpoint and quiet shades of repose.

Any composer who sets out to write a really good wind quintet contends with inherent challenges of the instrumentation, chief among them the balance of sound between the high, light sound of the flute and the potentially low and overwhelming sound of the French horn. But they also have a beautiful, diverse palette of colors and textures open to them, and it seems to me that this 1986 work for winds makes use of these with aplomb. It’s a very enjoyable piece that moves in three main sections through bubbly counterpoint and quiet shades of repose.

Though the played-out “train chugging along through the night” concept seems to pop up incessantly in contemporary music for wind ensembles, I’m happy to give Adolphe a pass here since the piece was initially conceived with no specific inspiration in mind. The flickering colors and shifting mosaic of rhythm that characterize the music that opens and closes the piece seem to evoke a darkened nighttime landscape passing outside the window of a train, and thus the composer chose Night Journey for the title.

– Geoffrey Larson

Tune in to Second Inversion in the 9pm hour today to hear this piece.

Half hypnotic, half neurotic, Philip Glass’s Mad Rush for solo piano is a minimalist masterpiece. He first premiered the piece in 1979 for the Dalai Lama’s first public address in North America—because his actual arrival time was so vague, they needed music that could be stretched for an indefinite period of time. Thus was born one of the most iconic piano pieces of the late 20th century.

Half hypnotic, half neurotic, Philip Glass’s Mad Rush for solo piano is a minimalist masterpiece. He first premiered the piece in 1979 for the Dalai Lama’s first public address in North America—because his actual arrival time was so vague, they needed music that could be stretched for an indefinite period of time. Thus was born one of the most iconic piano pieces of the late 20th century. It’s been becoming increasingly clear to me lately that John Cage’s music can be an extremely powerful gateway into a different universe of listening. So, pieces like this one make more sense to me now than they used to. This piece, like Cage’s music, is an inducement to listen with open ears – a reminder to hear music for what it is. –

It’s been becoming increasingly clear to me lately that John Cage’s music can be an extremely powerful gateway into a different universe of listening. So, pieces like this one make more sense to me now than they used to. This piece, like Cage’s music, is an inducement to listen with open ears – a reminder to hear music for what it is. –

John Cage threw a wrench in the Western music tradition when he invented the prepared piano in 1940. Presented with the challenge of writing dance music for a small stage, he created his own percussion orchestra inside a piano by placing screws, bolts, and pieces of rubber between the strings.

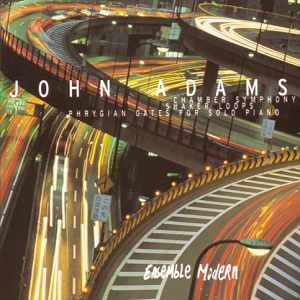

John Cage threw a wrench in the Western music tradition when he invented the prepared piano in 1940. Presented with the challenge of writing dance music for a small stage, he created his own percussion orchestra inside a piano by placing screws, bolts, and pieces of rubber between the strings. Sometimes, instead of a complicated meal full of newly-invented ingredients and prepared with exotic techniques, it is preferable to have a simple salad composed of greens, oil, and salt. John Adams’s Phrygian Gates is the musical equivalent of this, in my opinion. This piece confirms that a construction built from the simplest ingredients can unfold into a supremely delicious and satisfying experience. –

Sometimes, instead of a complicated meal full of newly-invented ingredients and prepared with exotic techniques, it is preferable to have a simple salad composed of greens, oil, and salt. John Adams’s Phrygian Gates is the musical equivalent of this, in my opinion. This piece confirms that a construction built from the simplest ingredients can unfold into a supremely delicious and satisfying experience. – Electronic music and modern composition collide in Treasure State, the collaborative album from Matmos and So Percussion. In “Flame,” a melancholy guitar and phonoharp are joined and propelled by ripples of vibraphone, glockenspiel, and stomping as the song transitions from alluring to pure cacophony.

Electronic music and modern composition collide in Treasure State, the collaborative album from Matmos and So Percussion. In “Flame,” a melancholy guitar and phonoharp are joined and propelled by ripples of vibraphone, glockenspiel, and stomping as the song transitions from alluring to pure cacophony.  An early 20th century lithograph, entitled “Dance in a Madhouse,” depicts a scene in an insane asylum that inspired composer David Leisner to write four dances for the highlighted patients. The first movement, “Tango Solitaire,” is for the stylish woman dancing solo in the center of the frame. “Waltz for the Old Folks” corresponds with the happy couple in front of her, who seem completely comfortable with their insanity. Third, “Ballad for the Lonely” represents the despairing women on the sidelines, and “Samba!” is for the couple on the left, dancing with wild, dizzying energy.

An early 20th century lithograph, entitled “Dance in a Madhouse,” depicts a scene in an insane asylum that inspired composer David Leisner to write four dances for the highlighted patients. The first movement, “Tango Solitaire,” is for the stylish woman dancing solo in the center of the frame. “Waltz for the Old Folks” corresponds with the happy couple in front of her, who seem completely comfortable with their insanity. Third, “Ballad for the Lonely” represents the despairing women on the sidelines, and “Samba!” is for the couple on the left, dancing with wild, dizzying energy. To say sound-sculptor Trimpin likes to think big would be an understatement—installations like a six-story-high xylophone, a tower of approximately 500 guitars (housed at Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture), and an 80-foot installation that responds musically to the motions of passersby are just a few of his musical inventions.

To say sound-sculptor Trimpin likes to think big would be an understatement—installations like a six-story-high xylophone, a tower of approximately 500 guitars (housed at Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture), and an 80-foot installation that responds musically to the motions of passersby are just a few of his musical inventions. Mamoru Fujieda’s Patterns of Plants series is born of a fascinating, elegant creation process: an exquisite combination of nature and technology. The composer worked with the “Plantron,” a device created by botanist and artist Yuuji Dogane that measures electrical fluctuations on the surfaces of leaves of plants, and converted the resulting data into sound using computer programming. Through a process he has likened to searching “in a deep forest” for “beautiful flowers and rare butterflies,” Fujieda listened for musical patterns, and used them as the basis for composing short pieces, which he then grouped into collections reminiscent of Baroque dance suites.

Mamoru Fujieda’s Patterns of Plants series is born of a fascinating, elegant creation process: an exquisite combination of nature and technology. The composer worked with the “Plantron,” a device created by botanist and artist Yuuji Dogane that measures electrical fluctuations on the surfaces of leaves of plants, and converted the resulting data into sound using computer programming. Through a process he has likened to searching “in a deep forest” for “beautiful flowers and rare butterflies,” Fujieda listened for musical patterns, and used them as the basis for composing short pieces, which he then grouped into collections reminiscent of Baroque dance suites. “Far Islands” is the perfect song for stress relief. Quentin Sirjacq’s enchanting minimalism gives one room to breathe and contemplate the spaces in between the sparse piano plucks and fuzzy synthesizer. Sirjacq once stated that his music “is neither nostalgic nor romantic, but ‘reminiscent’”—this is a perfect description. His delicate composition here is reminiscent, to use his word, of peacefully floating in a warm lake; it loosens the tension in your muscles and readies your mind for leisure. Listening with a glass of wine in hand would be perfection. –

“Far Islands” is the perfect song for stress relief. Quentin Sirjacq’s enchanting minimalism gives one room to breathe and contemplate the spaces in between the sparse piano plucks and fuzzy synthesizer. Sirjacq once stated that his music “is neither nostalgic nor romantic, but ‘reminiscent’”—this is a perfect description. His delicate composition here is reminiscent, to use his word, of peacefully floating in a warm lake; it loosens the tension in your muscles and readies your mind for leisure. Listening with a glass of wine in hand would be perfection. –  As the second movement in Glass’ famed six-part chamber work, Glassworks, “Floe” holds a place of esteem in its own right, featured in the 1989 Italian horror film, The Church.

As the second movement in Glass’ famed six-part chamber work, Glassworks, “Floe” holds a place of esteem in its own right, featured in the 1989 Italian horror film, The Church.  If you don’t have five hours to listen to John Cage’s sprawling, narrated sound art piece

If you don’t have five hours to listen to John Cage’s sprawling, narrated sound art piece